Back in the Saddle Again

We can rebuild him. We have the technology…

This is my 100th Substack article, and I figured it deserved something a little more special than yet another installment of Raspberry Pi rigs keeping the tomatoes alive. Experience has taught me to keep the intimate details of my personal life off social media, but I’ll let a little of the fun stuff slip through this time.

This one’s a little more personal.

And like everything else I publish here, the point is still the same: live your own life instead of outsourcing it. If you read my Be Trained… or Be Chained piece, you know exactly where I’m coming from.

Long Miles of Hard Riding

Growing up in Boston in the 70s, I learned early that the streets didn’t hand out second chances. Tough neighborhoods, late-night subway rides home after sneaking into MIT to mess around on computers, you had to know how to handle yourself.

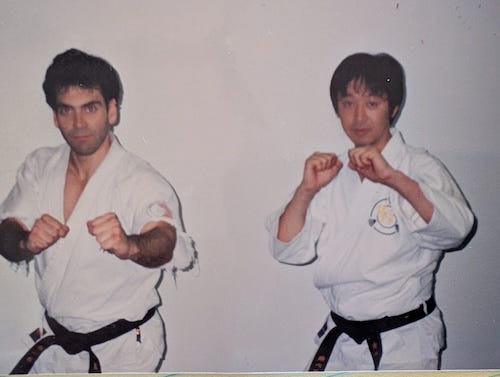

My dad sent me to my first martial arts school in the 70s, a little place called American Combat Karate in Roslindale Square. Like a lot of dojos back then, it came and went, but it was my starting point. Martial arts didn’t come naturally to me, but I stuck with it long after plenty of others drifted off.

Eventually that path led me into Kyokushin-kai, training alongside folks with… let’s just say unconventional resumes. This was bare-knuckle, full-contact work with no illusions attached. You get comfortable with pain, maybe even a little friendly with it.

After Kancho Oyama died, the Kyokushin world fractured into camps I wanted no part of. I kept training and teaching for a while, but the real value was never the stripes on the belt or the size of the guy trying to knock your head off. What mattered was the discipline, staying focused, keeping your head when everything hurt, pushing through when most people quit..

On Any Sunday

Some of the guys I trained with turned me on to motorcycles. I respected what they were capable of, but the lifestyle was not for me. What I did take from them was the focus, the discipline, and the way riding demanded the same clarity you needed in a fight. One of them also pointed me toward the MSF RiderCourse, which turned out to be exactly the kind of structured, no-nonsense training I needed to start the right way.

I loved the course enough to go back and apply to be an instructor. That program was no easy path, with an attrition rate on par with what you’d expect from a military selection course. The school was particular for good reason. Some of it was liability, but a lot of it was because you were dealing with civilians who do not always realize how quickly a motorcycle can punish bad decisions. We had to be perfect.

Motorcycles became a prime focus for me, and there were days when my life looked like On Any Sunday with a punk rock soundtrack. The downside was that between teaching karate, teaching at the motorcycle school, and working as an engineer, I had no time left for anything that passed for normal life.

Back then, my mistress was a Kawasaki ZX-11 — a vicious, beautiful beast that hit 175 mph and could go from zero to dead in the length of one stupid mistake. She didn’t forgive sloppy throttle hands or late braking. That bike scared the hell out of me just enough to make me get real serious. I signed up for the California Superbike School. where I earned more from Keith Code than I could have ever expected. He stripped racing down to its bones and rebuilt it as this perfect blend of engineering and art. But also his teaching methods showed me how to train people with precision instead of guesswork.

It was not long before I said goodbye to the east and headed for the sunny beaches of California. And before I knew it, I was spending whatever I could scrape together on tires just to get more time at Laguna Seca, and getting way more familiar with hay bales on the side of the track than I preferred.

Cold Work, Mountains, and Heavy Packs

California could not last forever. It eventually got Californicated, and it was time to buy a house and have kids, so we headed north. Southern Oregon has beautiful mountains and rivers, perfect for getting outdoors and pushing yourself a little. And I pushed. Most weekends I was on Mt Ashland, at Crater Lake, up Shasta, or grinding out miles on the PCT. I especially took to hiking the backwoods parts of the mountains where no one with any sense goes, especially in the snow. I liked experimenting and sharpening my wilderness survival skills whenever I could, usually with a heavy pack and a pair of snowshoes that were quietly filing warranty claims against my hip joints.

Every so often I crossed paths with the Jackson County Sheriff’s Office Search and Rescue team. Quiet professionals who get things done. They proved that again during the 2020 Almeda Fire, when entire neighborhoods disappeared in a matter of hours, taking more than 2,600 homes and 3,200 acres with them.

Seeing them operate made me want to contribute. I had mountaineering experience and a medic-EMT background, and I walked away from Silicon Valley to volunteer as a Search and Rescue professional and focus on problems that actually matter.

It felt good to finally be doing something real again. The kind of work that stays with you. Unfortunately for me, it also stayed with my joints.

Sooner or Later, You Gotta Pay the Bill

Some of the things that made life fun were also the same things quietly sending the invoice. Years of full-contact sparring, the crashes I survived on pure stubbornness, the heavy squats and deadlifts in my fifties, and all those snowshoe hauls straight up the mountain with a pack that weighed as much as a small human. It all adds up.

Then one day in a lumberyard I tripped on a 2x4 sticking out of a bundle. It caught me at a bad angle, one I couldn’t roll out of. I walked it off like I was conditioned to, but the pain kept dogging me.

For a long time I told myself it was nothing. The fun hadn’t disappeared; it had just gotten harder to fake. Training got uncomfortable. Standing for any length of time started to suck. Bending over to pick things up got harder than it had any right to be, and I wasn’t moving the way I used to.

Eventually I gave in, and as the song says, “Doctor, doctor, Mr. M.D., now can you tell me what’s ailing me”… besides the obvious.

The doctor didn’t need long. One look at the X-ray and he was amazed I could walk… let alone do any of the stupid things I’d been doing. I wasn’t just out of oil. The bearings were gone, the races were chewed, and the whole assembly was grinding itself to death. Or for you tech types: classic bone-on-bone contact, a femoral head that wasn’t even round anymore, and it was grinding straight into the acetabulum.

I kept kicking the can down the road until I moved to Arkansas, where health insurance didn’t require a second mortgage. “If you’re gonna be dumb, you gotta be tough.” I had both sides of that equation covered.

I was still running the old program: if something hurts, ride harder, lift heavier, push through it. That worked fine in my twenties and thirties, and to some extent even into my fifties.

We Can Rebuild Him…

I carry a hard distrust of institutionalized medicine after COVID, watching doctors who damn well knew better cave and parrot nonsense while pretending immune systems did not exist.

So I was very selective. I found a surgeon with real experience doing this work. This is what he does. He replaces hips day in and day out, and he has done thousands over his career.

Total hip arthroplasty. I started with the left side, and I was first up that morning. I rolled into the shop at 6 AM, was in pre-op by 7, on the table by 8, and the whole thing took about 45 minutes, maybe a little longer. When I came to in recovery, they already had the room flipped for the next guy. An hour or so later, they rolled me back to my room like nothing happened.

I was in my room babbling at the nurse before my brain had even rebooted. PT rolled in next, had me walk a lap or two around the nurses station with a walker and go up and down a few steps, and that was it. They kicked me out and sent me home.

The pain was fun. No it was not. Life sucked for a few weeks. I do not do narcotics, so I gutted it out on ibuprofen and acetaminophen, shuffled around in their goofy hospital socks, ditched the walker after a couple of days, and switched to a proper gentleman’s walking stick a buddy made for me. I actually had fun visiting the physical therapy (PT) lady a few times. They were nice folks, but I definitely was not their usual customer. I was back in the gym before long, and ten months later I knocked out the right hip. That one was even easier and I did my own version of PT.

If you want to see what the procedure really looks like, and you have the stomach for it, here is the link. Mechanically, it is not far off from replacing the ball joints on a 69 Camaro.

Back in the Saddle

Steve Austin got bionics. I got 3D printed TriTanium and delta ceramics. Now it was time to run it and see what the upgraded frame could handle. I did my time in the gym, regaining flexibility, strength, and movement. The goal all along was to see if I could swing my leg over a motorcycle and ride again. I swung a leg over Caleb’s Yamaha FZ-07 and rolled out like nothing had ever happened. With no bone restrictions, I moved smoother than I had in decades.

I had promised myself that if I could recover, I would reward myself. So I decided the reward was going to be a bike of my own. The question was what to get this time? Now that I was sporting grey hairs, I figured maybe I was supposed to want a cruiser. I threw a leg over a few. They handled like furniture. It is just not me.

Then one day I was dropping off the farm’s Kawasaki Mule for maintenance and wandered over to the bikes. I still miss my ZX-11. Then I spotted it. The KLR-650. It looked simple, durable, and ready to be ridden hard. My kind of machine. I knew the bike the second I saw it; I’d ridden the first-gen models back when they were brand-new and I was still teaching the course.”

What is a KLR-650?

The Kawasaki KLR650 is a legendary dual-sport/adventure motorcycle that has been in continuous production since 1987, making it one of the longest-running motorcycle models in history. It sports a 652 cc four-stroke, DOHC, dual-counterbalanced, single-cylinder, liquid-cooled engine. A thumper. Not much finesse, but plenty of torque and stupidity-proof reliability. And the current third generation models are fuel injected. They are not fast. They are not refined. But they are built to fire every time you hit the starter and run on whatever questionable gasoline you find in a rusted can in the middle of nowhere.

A big single like this means fewer moving parts. Fewer failures. Less to break, more to trust. People joke that you can fix it with a rock, but that is only funny because it is true. The thing was built to be dragged across continents by riders who pack duct tape, zip ties, and maybe a crescent wrench if they feel fancy.

It is a bike for people who want to go places instead of polish chrome. A bike for people who fix problems instead of complain about them. Especially when they involve dirt roads, bad decisions, and a long ride home.

The thing is, the KLR is not great at one thing, but it is very good at a lot of things, which is what actually matters in my world.

There are many like it, but this one is mine.

I call him Thumper. I rode home from the dealer, then spent the next couple days boring holes in empty parking lots with my old MSF instructor range cards tucked in my pocket: slow circles, quick stops, figure-eights; just knocking the rust off and proving to myself the new hips still knew how to dance.

Usually I can’t leave anything stock for more than an afternoon. This time I kept it simple: Enduro Engineering Skid Plate and Linkage Guard and a set of Barkbusters Handguards. And that custom Thumper decal that still makes me grin every time I throw a leg over.

Soon it was time for a real ride, and in one perfect moment I knew I was truly back. Everything clicked. Rolling the throttle down a quiet country road, the engine answered instantly, my body moving with the bike like it always had. Look deep into the curve, turn, and burn. The road opened up and the years, the surgeries, the pain; everything just melted away. It was just the bike and I, exactly where I needed to be.

Some things do feel different now. My body has new parts and limits, and I let that make me a better rider, not a slower one. I’ve traded reckless abandon for hard-earned wisdom. I ride smarter, sharper, and with more focus than ever.

But some things are exactly the same. That engine still has its own heartbeat. The way the chassis leans, the wind in my face, the pure connection to the road; none of it has changed. Riding still brings clarity. Riding still feels like freedom.

This isn’t nostalgia. This is a declaration.

Proof that the work mattered. Proof that I’m still the one holding the handlebars, not the doctors, not the diagnosis, not the slow creep of age. I did the rehab, rebuilt my body, and threw a leg over the bike again because that’s who I am.

It’s the same principle I’ve written about before: independence is earned, not given. It’s all about taking ownership of your life, your body, and your choices. On the road and off.

This post fits into the bigger picture of what I write about.

For the broader mission—start here: Independence: built from code, steel, and stubbornness.

Be sure to document the serial numbers on your new parts in case you need it in the future.