Parts that don't suck: part 1

Making good connections.

I’ve built a lot of projects over the years. Some worked the first time. Some didn’t and just needed coaxing with a bigger hammer. What I learned is that while most electronic parts technically work, a lot of them only work long enough to pass a bench test, then quietly screw you later when the system is cold, hot, vibrating, wet, or you’re 20 hours into a 10-hour shift.

This series is about parts that didn’t pull that crap. Every now and then I run across something I really like working with because it’s easy to use, well thought out, and takes all kinds of abuse while keeping on ticking.

Let me also say this up front. Like most things I write, these are my opinions. You are not only allowed to disagree with me, I encourage it. And if you have a part you trust that I do not mention, drop it in the comments. Maybe you’ve learned something I haven’t yet. That is how this works.

And to be clear, no sponsorships. No affiliate links. No favors. I am pretty sure most of these companies have never heard of me, and that is fine. I am writing this because these parts earned their place in my shop, not because anyone asked or paid me to.

Now that that’s out of the way, let’s dive in.

Anderson Powerpole.

If you’ve spent any time around ham radio, emergency comms, or portable DC power in the US, you already know these. If you haven’t, you should.

Powerpoles come from Anderson Power Products, a company that’s been building high-current connectors for industrial use since the mid-20th century. Their connectors show up in forklifts, battery systems, and industrial chargers, and they come in a wide range of sizes, from connectors you can weld with down to ones you can hold between two fingers. Anderson Power Products started in Boston and, by 1972, had moved manufacturing to Sterling, Massachusetts, where they are still based today.

The ones most people recognize, and the ones I’m talking about here, are the 15/30/45 Amp Powerpole. These weren’t originally designed for hams. It was simply a solid modular DC connector with good contact pressure, silver-plated contacts, and a housing that didn’t care which side was “male” or “female.”

Kind of like some of my neighbors when I lived in Ashland.

Then ARES, RACES, and ham radio groups did what they always do. They standardized and settled on a single orientation. Hold the connector with the locking tongue up, red on the right and black on the left. Suddenly, gear from different people just plugged together and worked.

Hams love these because a properly crimped Powerpole will carry up to 45 A on 10 AWG wire. Even though I often run them at much lower current, I still use the proper crimping tool so a bad crimp does not bite me in the ass at the worst possible moment.

And for the record, Anderson has made Powerpoles in much larger sizes, up to 350 A long before the smaller versions became common in ham radio. I have used the larger ones myself in a few 4WD truck builds for winches.

Quick note on Powerwerx, since their name comes up a lot around Powerpoles. They’re not the manufacturer, but they’re a reliable source of Powerpole-related parts, wire, and other useful gear, with great customer service.

One thing to keep in mind, Powerpoles are not sealed connectors. Rain, salt air, and mud will eventually win. In those environments, I reach for something built to live outside.

Deutsch DT Connector

Deutsch DT is the gold standard for rugged, sealed multi-conductor connectors used in automotive, off-road, and industrial gear. They keep working when things shake, heat up, and get wet. You’ll find them everywhere from tractors and bulldozers to race cars. I even use them on my farm’s irrigation system.

Deutsch Industrial was founded in 1938 by Alex Deutsch in Los Angeles, California, building electrical connectors for trucks, heavy equipment, and military hardware. This was the world of diesel engines, fleets, and outdoor machinery, where a wiring failure has real consequences.

By the 1950s, Deutsch was building sealed, serviceable connectors for military and aviation use, with removable contacts and positive locking. Those ideas evolved through the 1970s and 1980s into the DT series, a sealed multi-pin connector system built for harsh environments. In 2012, Deutsch was acquired by TE Connectivity, where the DT line became part of its automotive and industrial connector portfolio.

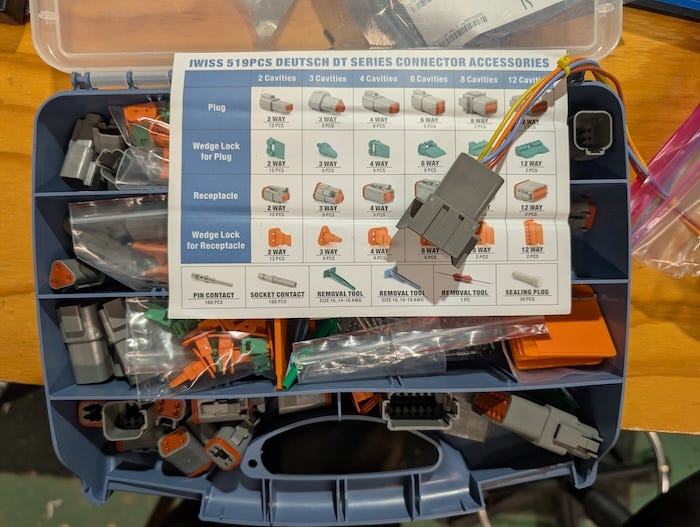

I’ve used DT connectors in my Raspberry Pi Car Radio Project and around the farm, where weather and vibration are just part of the deal. These days, getting started is easy. You can easily find starter kits on Amazon with housings, pins, seals, and a basic crimper all in one box. It’s enough to learn the system and build real harnesses without hunting part numbers.

Another popular sealed connector system is Weather Pack, along with its follow-on Metri-Pack family. Developed by Delphi Packard,, they came out of the Detroit OEM world and were optimized for high-volume automotive production. Fast to assemble, cost-controlled, and often just durable enough to outlast the car loan, not the car.

I have used both systems, and while the Weather Pack seems more common in US OEM automotive harnesses, I tend to lean towards the Deutsch DT when vibration, moisture, and long-term reliability matter more than assembly speed.

Blue Sea ST Blade Fuse Block

Once you’ve got reliable connectors and solid harnesses, the next thing you want to deal with is circuit protection. No matter how good your wiring or how clever your design, unprotected circuits will fail spectacularly when something goes wrong. That’s where fuses and fuse blocks come in. They keep projects organized and accessible, and they keep shorts from turning into blown gear or melted wiring.

My time working with marine electronics, and from books like Boatowner’s Mechanical and Electrical Manual, taught me a lot about building safe, well-protected power circuits.

One of the places those lessons show up over and over is in how I handle power distribution. A clean, well-protected fuse block makes everything downstream easier to reason about, easier to service, and harder to screw up. One of my go-to parts for that job, which I’ve used everywhere from Jeeps and well pumps to chicken coops, comes from Blue Sea Systems.

Blue Sea Systems has been building marine-rated electrical components since 1992 out of Bellingham, Washington. Their lineup covers AC and DC power gear like battery management, circuit protection, busbars, switches, and fuse blocks, all designed for harsh environments.

The specific part I keep coming back to is their ST Blade Fuse Block, especially the version with a cover and a negative bus. I particular like this because it allows me to the power distribution wiring clean, organized and easy to service. It uses standard automotive ATO and ATC blade fuses, which are cheap, easy to find, and easy to replace in the field, and the cover keeps fingers, tools, and stray debris out while still letting you see what’s going on.

You might also want to poke around Blue Sea’s website. The tools and reference material are genuinely useful when you’re laying out power systems and trying to do it right.

Coincidentally, another company out of Bellingham, Washington worth mentioning is Ancor. They make tinned copper wire and heavy-duty connectors that hold up in harsh environments. I’ve certainly spent more than a few bucks at West Marine on their gear over the years because it survives corrosion and vibration where ordinary automotive parts fail. These days, you can find the same stuff online too.

I haven’t tried every brand out there, but tinned copper is the key detail. If the wire is truly marine grade, it will hold up better anywhere moisture and corrosion are part of the deal.

These parts earned their place in my shop. Nobody asked. Nobody paid. More to come.

If you care about how things are made and why they’re built the way they are, you’ll probably like the rest of what I write about. Hitting like or sharing helps real people find the work. The algorithm can go pound sand.

Absolutley love this rundown on parts that actually deliver when stuff gets real. The whole idea that some connectors are built to weld with while others fit between your fingertips really hammers home how mission-critical sizing is for current loads. I've had way too many projects fail in the feild because I underestimated vibration and moisture over time. That shift from "passes bench test" to "survives 20 hours into a shift" is such an underrated design philosophy that seperates hobbyist gear from pro-grade hardware.